‘Unwild Wales’ was my original, slightly provocative title to ‘Tir’ (which comes out now in six short weeks!) It was a deliberate provocation though – not just an allusion to George Borrow’s 19th century jaunt through the country and subsequent long-burn bestseller on Wales from the outside, but also to current hot debates on land use and wildlife in Wales.

One of the salient points about that current debate, contested and high-stakes as it is, is the extent to which people bring different cultural frameworks and reference points to bear on it. In this sense, there seemed to me to be a deeper underlying link with Borrow’s recounting of his experiences in the 19th century, and his depiction of Wales as above all ‘wild’. He may well have chosen that adjective with his tongue firmly in his cheek, given his knowledge of and affection for Welsh culture. But he was at any rate tapping into a trope that was already well-established by the time he was writing, whereby Wales had long since been imagined from the outside, and experienced by outside visitors, as the epitome of wilderness – or at least, as the epitome of wilderness-near-at-hand. (The answer to the question, ‘what does wilderness look like when it’s only a day’s coach travel away from London?’)

There were of course reasons for this, to do with ‘backwards’ conditions in the bulk of Wales’ mountainous and resolutely non-English speaking interior. Unlike the Alps, Wales was not home to long established trans-continental trade routes. It had no major cities to speak of, nor an urban bourgeoisie that represented its own power centre. On the other hand, it was not ‘heathen’ as for much of western European history the Baltic countries or Africa were perceived to be. There was, in other words, a long memory of Wales being near-at-hand and approachable while also not conforming neatly in terms of its ways of life and culture to western European norms.

The extent to which this has been a long-standing phenomenon can be seen in a 13th century encounter between Stephen Lexington, Abbot of Stanley and Clairvaux, and the monastic community of Whitland Abbey. Abbot Stephen objected strongly to the Welsh monks’ practices, asserting that they were more concerned monks in associated monasteries spoke the Welsh language, ‘than that they do the will of God and the order’.[1] To readers in the 2020s, with sixty years of prominent language activism behind us in Wales, this may seem unsurprising. Given, though, the vast cultural gulf on so many other fronts between today’s Wales and that of the high Middle Ages, this medieval clash of worldviews within the regulated confines of a monastic order is noteworthy. It betrays of course a difference of outlook between Stephen and the Welsh monks on the question of language, and this I think contains an important nugget of insight that applies, mutatis mutandis, to perceptions of land use and nature too.

We could get at that quite neatly by reflecting on the simple question of what a landscape is. To the 18th century artist, Paul Sandby, the mountainous north Wales landscape was the epitome of the picturesque, with as Schama puts it, ‘the language spoken by the natives [heard] as the phonetic equivalent of the landscape.’[2] It was, in other words, a place that through all the senses took you outside the normal realms of civilised life and into something ineluctably different – slightly barbaric, perhaps, and ‘wild’.[3]

Interesting though this all is, and perpetuated though it continues to be (in guidebooks and tourist writing), it also when viewed from a certain angle becomes almost unbearably comic. The particular angle I have in mind – and one I cannot given my own upbringing get away from – is that of Welsh (language) culture, the inhabitants of which had, have and have left an almost diametrically opposed way of experiencing, viewing and interpreting the Welsh landscape.

There was and is in this culture an utterly assumed familiarity with the landscape, rooted above all in the culture’s sense of its own continuity within it. This familiarity, as I explore in the book, can be seen from the earliest written records we have in Welsh from the 1st millennium AD and is amplified from that point forward throughout the cultural record. Its expression is utterly varied in nature, ranging from the onomastic tradition of poems and myths explaining place-names, through to medieval poetic theorizing on Welsh princehood whereby the term ‘marriage’ (priodas) was used to denote the connection between ruling princes and their land.[4] It formed a dense web of association, that manifested in the early modern period in traditions linking geographical boundaries with the supernatural[5] and in ongoing cultural practice that identifies individuals and families in conversation through the names of farmsteads and places. Perhaps the most striking modern expression of this is the continuing cultural salience of Dafydd Iwan’s ‘Yma o Hyd’ ballad, that draws on repeated Welsh myth-making going back to the late 4th century ‘Magnus Maximus’ of Wales and Rome; the key point here being that it is the emphasis on the Welsh being ‘here’ in the land that clearly resonates with the boisterous crowds.

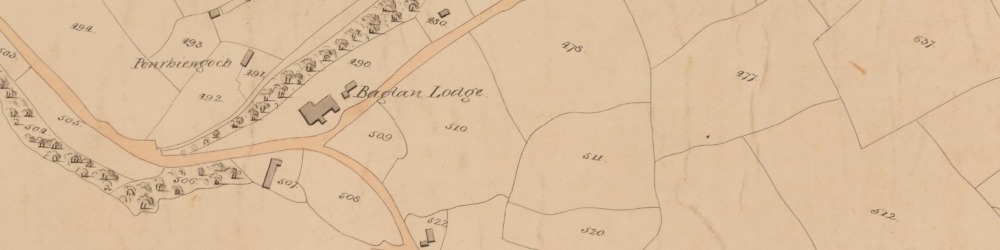

This is all the domain of cultural narrative, but it corresponds interestingly with archaeological consensus that the land-mass of Wales been settled since well before the beginning of recorded history. As cropmarks in hot summers continue to testify, the landscape even of poorly endowed Ceredigion shows dense settlement by the Iron Age[6], with much of the land by then already in continuous use for thousands of years. The combined archaeological and documentary evidence we have is of continuous settlement, with all that implies for farming and wider land-use for timber, firewood and textiles at a minimum. This point should not be taken for granted; it stands for instance in sharp distinction to what we know about early medieval Germany, where the knowledge of manuring seems to have been lost by 6th century meaning settlements had to be moved around the landscape every three generations or so.[7] In Wales, as I explore in the book, there is every suggestion that the oldest inhabited spots across the landscape have remained so without a break for, now, thousands of years.

This matters not only for our understanding of Wales but particularly when it comes to current environmental questions of civilizational import. Here, much of the discourse that is amplified and repeated across the western world is anchored in analyses of modern human ecological impact in the USA, Australia and so on, where the cultural-environmental dynamics through colonialism are vastly different. I have much time for Wendell Berry’s writings and reflections; but so much of what they take for granted as environmental backdrop simply does not apply here in Wales. What does apply is a narrative that recognizes first of all a long history of being settled; a profound absence of wilderness; and an often painfully defiant culture that asserts its own right of place here. From that narrative, we can start asking important questions about the balance between domestic life (and animals) and wildlife, between human knowledge of a place and its own ‘natural’ dynamics, between using a landscape and celebrating it, and so much more.

This was some of what I wanted to open up in the book – out now in 6 weeks’ time…

[1] p.128, Williams ‘The Welsh Cistercians’

[2] p.469, Schama ‘Landscape and Memory’

[3] There is, of course, nothing uniquely Welsh in this experience. There is an enormous literature examining the ways and extents to which this has been the case for cultures throughout the world over the past few centuries and indeed in the ancient world. The word ‘colonialism’ can’t be kept too far from such a discussion.

[4] p.140 in ‘Ar drywydd enwau lleoedd’

[5] pp47-69 in Badder and Norman, The Folklore of Wales: Ghosts

[6] p.4 Driver, Iron Age Hillforts of Cardigan Bay

[7] p.29 Brunner in Ed Sweeney, Agriculture in the Middle Ages