This series of posts is exploring Welsh food culture, as it developed from the time of the earliest written records through to the 20th century. Much has changed in the last 50 years, so that only vestiges now remain of ways of growing, preparing and sharing food that had previously united much of the country in shared dishes and culinary cultures. The last post explored the tale of Sioni Winwns, onion growers from north-western Brittany who came to sell their sweet onions to Welsh housewives from the 1820s. This set me thinking of vegetable growing in Wales at the time….

The most iconic of Welsh dishes, cawl, depends above all on vegetables. Leek, swede, carrot and potatoes may be unromantic (by dint of sheer familiarity: they are exotic enough viewed through Filipino or Yemeni eyes), but they also have long tradition behind them in Wales. Cultivating gardens, growing and using veg are a neglected part of Welsh food culture that deserve much more attention than they have traditionally received. Victorian Welsh society, to pick up the thread of Sioni Winwns’ early visits to Wales, was known for industry and for its distinct nonconformist chapel culture. Wales was a core part of the British Empire, and from the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 onwards, cheap imports of food flooded into the country, altering and perhaps distorting the market for native-grown produce. Nevertheless, Wales had a long-established tradition of vegetable cultivation, both for culinary and medicinal use, which from the 18th century until after the Second World War allowed a small native industry of market gardeners and nurseries to flourish (see list here of Welsh market gardens and nurseries)

Market gardening in England only started to become an established branch of agriculture from the 1650s, after a period of steady growth in vegetable consumption over the previous century, and the realization that in years of poor harvests a plentiful supply of vegetables could mean the difference between survival and starvation.[1] Records are too scanty to ascertain when the first market gardens appeared in Wales during this period. The earliest market garden in Wales that I can find mention of is Early’s Garden in Cowbridge, in a passing reference in 1738. But the culture of vegetable growing was already long-established in Wales by the time of the broader horticultural renaissance of the late 17th century.

The roots of growing vegetables in small plots for consumption in the home or on the estate almost certainly lie before our earliest written records, as both archaeological and linguistic evidence and Roman-era documents suggest. By the time of the laws of Hywel Dda, which remained in force in the country until the Acts of Union with England in 1536, vegetable cultivation in Wales was widespread enough to necessitate specific regulation. These include provisions for farmers to fence fields and gardens, and leeks – along with cabbages – are one of the few crops singled out for mention by name. Linguistic evidence in Middle Welsh supports this picture, with the now archaic word ‘lluarth’ – meaning vegetable garden – appearing frequently in medieval texts, along with ‘gardd fresych’ for cabbage garden. Alongside this cultivation of vegetables for the kitchen, there was clearly a strong native tradition of plant cultivation for various uses encapsulated in the records of the physicians of Myddfai who first appeared in the 13th century and whose tradition continued in various forms for some four hundred years. The notable feature of their writing, as opposed to other medieval collections of herbal lore, is their focus on native species of plant rather than only those known to classical writers in the Mediterranean basin. All of this suggests a culture that was familiar with plant cultivation and the different uses that could be made of garden plants – a picture I paint further in the opening chapter of Apples of Wales.

Consequently, although direct evidence for the establishment of market gardens in Wales during the 16th and 17th centuries is slim, there clearly existed a body of knowledge within Welsh culture for plant cultivation that was already widespread. Linguistic evidence also supports the view that market gardening as an occupation grew in Wales at around the same time as it did in southern England, with the terms ‘gardd fagu’ (plant nursery) and ‘gardd lysiau’ both making numerous appearances during this period for the first time.

By the late eighteenth century we are on much firmer ground. Walter Davies (Gwallter Mechain) mentions several nurseries and market garden enterprises in his reports into agriculture in South Wales published in the 1810s, and he makes no suggestion that most of these were newcomers on the scene. According to his report, the most important centre of market gardening in the Cardiff area, for instance, had become Llandaff:

‘The kitchen-gardens of the market-men at Llandaff, near Cardiff, are numerous and productive ; supplying the most convenient parts of South Wales, and in a certain proportion the Bristol market, with vegetables : such a group of gardens for the accommodation of the public, we have not noticed elsewhere within the district. To enumerate the several articles of the first-rate gardens, would be to write in part a botanical dictionary : the crops of a farmer’s- garden consist of the vegetables most appropriate to his table, viz. early potatoes, yellow turnips, early and winter cabbages, greens, varieties of pease and beans, carrots, onions, and other alliaceous plants, and varieties of salads; to which some add brocoli, cauliflowers, asparagus, seakale, rhubarb.’

The range of vegetables listed here is by Davies’ own admission only a part of what was known and grown. The presence of asparagus and salads on his list may go some way to dispelling some tired notions of historic Welsh fare. More telling still in this context are his remarks that ‘such a group of gardens’ are not seen elsewhere in the district, implying that although the Llandaff market gardens were exceptional in their extensiveness, that nevertheless single market gardens existed in other parts of South Wales, not to mention private garden and orchard plots. In the Teifi valley Felindre nursery was described as the ‘largest in the district’, operating on 18 acres. Over the fence, a competitor worked an 8 acre nursery. Nurseries and market gardens are not identical categories, but there is reason to believe that many businesses had a hand in both.

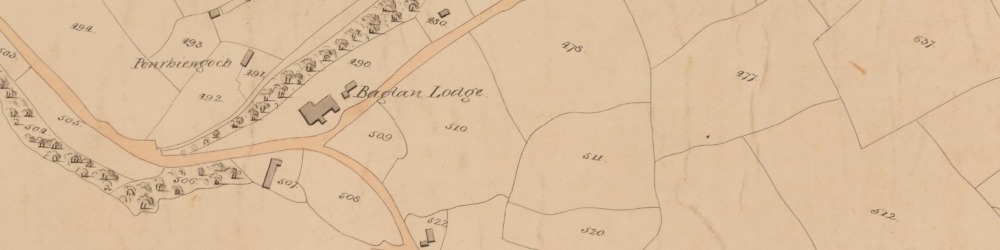

The 1836-1850 Welsh tithe maps confirm the general picture, with small plots of land labelled ‘garden’ around various Welsh towns, including Aberystwyth, Carmarthen and Cardiff. Some of the plots so labelled are located some distance away from the nearest house or cottage, implying by this point a small amount of vegetable production on a field scale. These maps deserve further study, but provide strong evidence for the spread of the burgeoning Welsh horticultural industry during the early decades of the 19th century, confirmed by a 1877 government report on land use across the UK. Here the acreage of Welsh market gardens was put at cc. 446 acres with another 367 acres of nursery grounds – compared to some 12,000 acres in England.[2] Market gardens are defined in this report as “land used by the gardeners for growth of vegetables and other garden produce, and as market gardeners are generally alive to the possibility of obtaining quick returns, and securing the most rapid succession of crops in, on, and above ground, the land so classed supports a considerable sprinkling of trees, and repays its cultivators by the variety of its fruit, root, and surface crops.”

In other words, a full range of garden crops were grown in these gardens, including leaves and fruit. The report goes on to note that Wales “has little over 3000 acres in orchards and market gardens put together; or considerably less than may be found in the large county of York” – which was at the time a few thousand square kilometres smaller in area than Wales. Of all the Welsh counties, however, only Anglesey is singled out for having no orchards[3] and Radnor alone as having no market gardens.[4] (Interestingly, Wales had significantly more acreage of land under orchard – 2619 – than Scotland, while Scottish market gardens come to 2939 acres, dwarfing Wales’ coverage).

There were therefore market gardens in almost all the counties of Wales by this point, though detailed information on where precisely these were found and what they grew is sadly lacking. After Walter Davies’ report mentioned above I know of no other account that mentions the crops grown in Welsh market gardens, or even the specific location of most of these growing sites. Partly this is to do with the well-noted fact that the railways enabled the industrial towns and cities of south-eastern Wales to be supplied by the Evesham horticulture industry, which was first established in the 17th century and benefited from economies of scale and a good climate for horticulture.[5] Welsh market gardens and nurseries continued to play an important part, however, in supplying some of the population’s dietary needs through the latter decades of the 19th century and well into the 20th century, becoming a familiar part of the landscape or townscape in many areas. As The Welsh Gazette notes on Jan 4th 1900: ‘market gardening is an old industry in and around Aberystwyth, and I don’t assume to teach old growers, who have learnt by experience the best methods and the best things to grow for profit. There appears to be a steadily growing demand for all kinds of garden produce, and the prospects for market gardeners in the district are good…’

Here we arrive back at the nub of the matter, insofar as this series of posts is concerned: in 1900 as in Hywel Dda’s time, Wales was home to a widespread, if slightly underdeveloped, culture of vegetable growing. Market gardening requires skill and practice, and is best learnt by imitation. It also requires a market, and at least between the late 18th century (though possibly earlier) and the early 20th century, there was a ready market for its produce across Wales. This, in short, is an important aspect of Welsh food culture as it adapted to early modernity. The extent of its neglect is shown in the fact that, to my knowledge, this short piece is the only study ever published in any language on the topic. I would be delighted to be corrected….

[1] Thirsk, Food in Early Modern England, pp. 59, 102

[2] Important to note here that England covers an area six times larger than Wales geographically – 21,000 km2 vs 130,000km2. If the same proportion of Welsh land were under market gardens as in England at the time this would have amounted to 2000 acres.

[3] Unlikely as orchards were known to exist at this point at Plas Newydd house and other estates – but the total acreage must therefore have been minimal)

[4] https://archive.org/stream/gardenillustrate1378lond/gardenillustrate1378lond_djvu.txt

[5] However, the old conker that vegetable growing didn’t fully take off in Wales because the climate and soils are simply unsuitable is misleading. The Vale of Glamorgan, Monmouthshire and most of South Pembrokeshire have very suitable climates for horticulture and rich soils, as do significant parts of the lowland NE, and the comparative lack of development has more to do with human factors than biophysical restraints.

Intresting blog post. The Cornish word for garden is ‘lowarth’ which is the same word as lluarth.

There would have been something of a crossover with mining. It is amazing to hear of miners who also had a smallholding and worked on the plot after a hard shift down at the mine. This may have helped with the fluctuating fortunes in mining, and often miners were on a ‘tribute’ system rather than a stable wage. There was quite a migration from Cornwall particularly to the lead mines in mid-Wales in the 19th century,

Great piece.As you say not much recorded but plenty to be discovered.Your note on unsuitable soils and climate cannot be repeated often enough.It was not an error that the Normans or William Marshall made.